Let’s say you live on the East Side of Cleveland and because of digital redlining, the fastest Internet service you can buy from AT&T is an ADSL2 connection that maxes out at 10 Mbps down and 1 Mbps up. What does that slow connection cost? As of July 2018, you’ll pay about $65 a month… $60 for the service plus about $5 in fees and taxes.

Let’s say you live on the East Side of Cleveland and because of digital redlining, the fastest Internet service you can buy from AT&T is an ADSL2 connection that maxes out at 10 Mbps down and 1 Mbps up. What does that slow connection cost? As of July 2018, you’ll pay about $65 a month… $60 for the service plus about $5 in fees and taxes.

Now suppose you live in Kamms Corners or Beachwood, there’s an AT&T fiber-to-the-node cabinet in your neighborhood, and your AT&T Internet is VDSL rated at 75 Mbps down and 8 Mbps up. Or let’s say you live in Bay Village, in one of the few local neighborhoods with access to AT&T fiber-to-the-home service, and your top speed is 100 Mbps down and 100 Mbps up. How much are you paying for 8 to 10 times the download speed and 8 to 100 times the upload speed available to that unfortunate redlined East Side resident?

You’re paying exactly the same: about $65 a month.

Find that hard to believe? Here’s a screen capture taken today from www.attsavings.com, an authorized AT&T retailer. We’ve highlighted AT&T’s $60 monthly rate “after 12 mos.” for all Internet speed tiers from 10 to 100 mbps.

The National Digital Inclusion Alliance has just released a new white paper, co-authored by CYC Director Bill Callahan, called “Tier Flattening: AT&T and Verizon Home Customers Pay a High Price for Slow Internet”. It begins:

Not so long ago, Internet Service Providers (ISPs) had “tiered” rate structures which offered significantly lower costs for lower speed limits. Most of us probably assume those tiers still exist in some form.

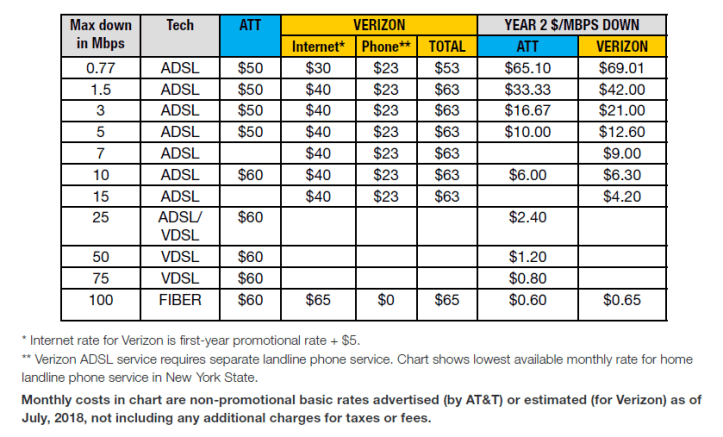

But, in recent years, the nation’s two largest telco ISPs, AT&T and Verizon, have eliminated their cheaper rate tiers for low and mid-speed Internet access, except at the very slowest levels. Each company now charges essentially identical monthly prices – $63-$65 a month after first year discounts have ended – for home wireline broadband connections at almost any speed up to 100/100 Mbps fiber service.

This policy of upward “tier flattening” raises the cost of Internet access for urban and rural AT&T and Verizon customers who only have access to the oldest, slowest legacy infrastructure. It imposes higher rates on millions of urban households who are relegated to slow ADSL technology by AT&T’s documented “digital redlining” of lower-income neighborhoods as well as Verizon’s refusal to deploy broadband upgrades in some entire cities like Baltimore and Buffalo. It also victimizes millions of underserved households in the two companies’ rural service areas.

Here’s an illuminating chart from the NDIA report that compares the cost per unit of service (i.e. per Mbps of download capacity) for AT&T customers at various speed tiers.

Is there some reason why Cleveland and East Cleveland residents who can only get 3 Mbps, 5 Mbps or 10 Mbps connections from AT&T, because the company failed to invest in modernizing its network where they live, should have to pay ten to one hundred times as much per unit of download capacity as customers in communities where AT&T did invest?